Passwords are the most common problem our customers approach us with. If we had a pound for every time we had to help someone reset or recover a lost password for an essential service, we would be on a tropical island somewhere sipping cocktails!

But passwords are so important, yet often the weakest part of someone’s computer security. Dr Mike Pound shows us in this video just how easy your password is to crack (heads up – this is technical stuff – if you’re not technical, ignore it and read on. Otherwise, for the more technical among you it’s interesting – and scary!).

So, hands up if you’ve used a pet’s name, or a date of birth, or your kids or partner’s name as a password. Keep them up if you’ve made a note of them in a ‘little black book’. Keep them up if you use that password on more than one service. Most of you? Thought so…

As Dr Pound says “Everyone’s passwords are terrible and they should change their passwords right now!”

In this article, Dave shows you how to create a secure password that you can remember, and how you’ll never have to remember more than one password!

The good news is, there are some really simple rules to follow to create secure passwords that are easy to remember. But first, a few ground rules for secure passwords.

A good secure password looks like this:

4c42y*lJ^

But is it easy to remember? Erm…no.

What makes it secure? The first rule is password length. The longer your password is, the better. My example is 9 characters. That’s probably the shortest possible to still be secure. I usually use passwords of at least 10 characters. Long passwords offer some (limited) protection against brute force attacks (trying every possible combination of characters until the right one is found).

The next rule is randomness. Hackers use a number of techniques to try to crack passwords. Usually, they’ll have some information about the person they’re targeting, so after trying the obvious things like ‘qwerty’ or ‘password’, they’ll try names, dates of birth etc. So don’t use any of these. The next thing they’ll do is use a dictionary attack. This is literally trying the most common words in the dictionary (and more increasingly some not so common ones). My example fits the bill on this score as well – but it’s not very memorable.

The next rule is variety. A secure password should have a combination of letters (both upper and lower case), numbers, and ‘special characters’. Special characters are anything that’s not a letter or number. Again, you can see that my example is very varied. The combination of variety and randomness offers really good protection against brute force attacks. In fact, I used an online tool to check the strength of it, and according to that it would take a thousand years (!) to crack using a powerful computer.

The final rule is uniqueness. You should never use the same password twice. Seriously. Here is a cautionary tale about why (even ‘techies’ like Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, can get hacked if they don’t follow the rules!).

But we still have the problem that a secure password isn’t memorable. This is really easy to solve, and there are a number of ways to do it. The best is to use a passphrase rather than a password. This could be the first line of a favourite poem or nursery rhyme, the title of a book or film, or a catchphrase. Anything really, as long as it’s a sentence. Let’s work through an example.

I’m going to use a phrase from the poem Jabberwocky:

“Twas brillig, and the slithy toves,

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe”

This is great, because it contains some words that aren’t in the dictionary. I could even use just those ‘nonsense’ words i.e. “brillig slithy toves”. That’s 18 letters that are quite easy to remember. Let’s put them together to form a word:

brilligslithytoves

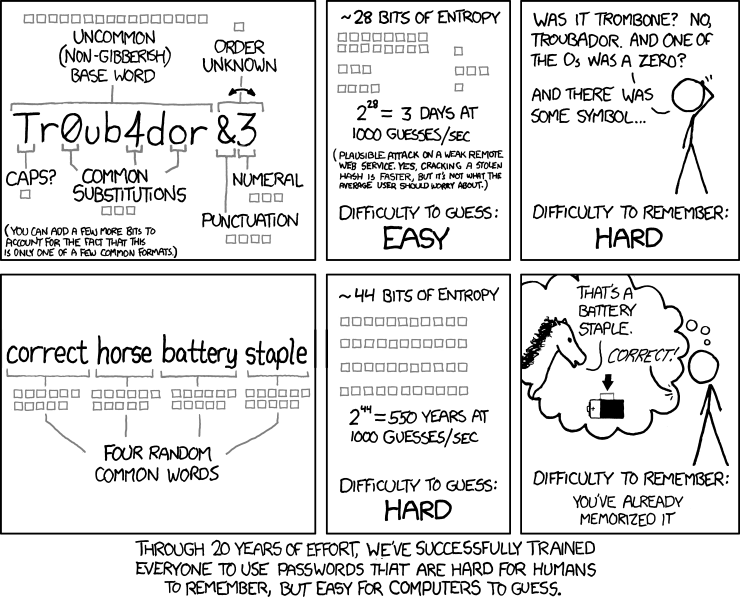

Now, on its own, that’s a really secure password (4 thousand years to crack). Randall Munroe at XKCD explains why with this comic:

I’m going to make it more secure by adding capital letters:

BrilligSlithyToves

7 million years – nice! I’m still not satisfied, so I’m going to substitute some of the letters for numbers (I usually pick a rule and stick to it such as ‘all i’s become 1’s’):

Br1ll1gSl1thyToves

83 million years! I think we can do better than that, so finally, add some special characters. Again, choose a rule and stick to it. I’m going to substitute l’s for !’s:

Br1!!1gS!1thyToves

There you have it. Apparently that would take 131 million years to crack!

There are other ways to do it. Taking those lines of poetry, I could choose the first letter of each word, thus:

tbatstdgagitw

Add some capitals:

TbatSTdgagitW

Substitute letters for numbers and special characters:

Tbat$Tdgag1tW

Bingo – 15 thousand years to crack that one! Nowhere near as good as our first effort, but still strong enough to make you average hacker give up and look for something easier to do, like count all the pebbles on a beach!

So we now have our secure password. But the temptation remains to re-use that across more than one online service. Remember, that’s a VERY BAD IDEA! There is a really easy way to deal with this, and that’s to add a suffix that represents each web service. For instance, if I wanted to use this on Amazon I could add :amzn, so my password becomes:

Tbat$Tdgag1tW:amzn

Wow, that now takes 16 trillion years to crack! I could use :sant for Santander, :pypl for Paypal etc. All you have to do is have a list of your suffixes, and maybe note down your substitution rules in your ‘little black book’ As long as you remember the poem, unless the hacker is a mind reader they’ll never guess the rest of your password.

Even if you don’t choose a password that takes trillions of years to crack, just using a string of words gives you a fantastically secure password that’s easy to remember. With a suffix on the end such as:

brilligslithytoves:amzn

I’ve got a password that will take 929 trillion years to crack with a brute force attack! Dr Mike Pound discusses this method, with some improvements in this video.

There’s an even better way to deal with passwords, and that’s to use a password manager. Dr Pound discusses this in his video shown above. A password manager is a small piece of software that plugs into your web browser, and remembers all of your passwords for you. All you have to do is think of a really secure ‘master’ password to unlock the vault, and that’s the only password you’ll ever have to remember. I use LastPass, but if you have a good paid-for anti-virus package, they often have a password manager as one of the tools included in the suite.

So just to recap the rules:

- password length. The longer your password is, the better. At least 9 characters.

- randomness. Don’t use dates of birth, names, strings of sequential letters and numbers, or the first 6 characters on your keyboard.

- variety. Use a mixture of upper and lower case, numbers and special characters.

- uniqueness. Don’t re-use passwords. Ever.

- passphrase. Use a phrase, or even just 3 or 4 words strung together. Spaces are allowed. Nonsense words are better.

- password manager. Offload the burden of remembering passwords onto a password manager.

Finally, and probably most important, don’t tell anyone your password. Not even your life partner. Relationships can go sour…

Be safe.

UPDATE: Adam at Safety Detectives contacted me to draw my attention to this Password Meter tool. You can either type in a password to measure its strength, or click the ‘Randomize’ button to generate a memorable password for you using some of the simple rules I have described above. It’s simple and effective – give it a try!